Entertainment

Freddy Will Gives a Breakdown of His Music

Published

3 years agoon

This article consists of two parts. We chronicle the creative method of a Grammy-nominated independent recording artist. Some know him. Many don’t. Freddy Will said he is a Mande. He dropped his first joint in 2006. As for his cultural environment, he is from Sierra Leone and raps in Krio and American English while combining old school Hip Hop with Afrobeat, Calypso, Soca, Rock, and Classical. Perhaps that’s why he describes himself as an Afropolitan who records and performs crossover Hip Hop.

We checked to verify the “City Boy” artist’s claims. Our investigation revealed that he had lived his life in stages. The first was when he was born in Brookfields Freetown, Sierra Leone, to a high school principal and a nurse. They became UN diplomats and Gospel preachers. Freddy entered his second phase when his parents moved to Liberia. There he received a Catholic education. At the same time, he was active in Church with his parents, learning to sing, compose, and play musical instruments.

This preacher’s son told us a friend introduced him to Hip Hop, but a civil war ensued. After some clashes with rebel militants, he entered the third phase of his life by returning to Sierra Leone. The gist of this part of his story is that he was separated from his family. They emigrated to the United States while he stayed with his father’s parents and relatives in Sierra Leone. He attended three secondary schools, Christ the King College, Methodist Boys High School, and Ansarul Muslim Secondary School.

We are sure there is a story. It could have something to do with the civil war. After running with the national soldiers, the preacher’s son graduated from high school. The Islamic school explains his reverence for Islam. Hip Hop was very unpopular in Sierra Leone in the early 1990s. Freddy Will’s conservative relatives opposed his adherence to the music culture. He was later one of many refugees who immigrated to The Gambia as the Sierra Leone civil war escalated. This was the fourth phase in his life journey.

In The Gambia, a teenager Freddy Will spent most of his time writing music and screenplays. He compiled volumes of handwritten Rhyme Books. Freddy briefly moved to Senegal to reconnect with an uncle before emigrating to the States to join his parents, grandparents, and siblings. His father is from the Loko people of Sierra Leone. His maternal grandmother was an African American of Guyanese descent. While his father’s parents lived in Sierra Leone, his mother’s parents lived in the United States.

We learned that Mande is an ethnic people from which various groups descend. They are Susu, Loko, Mandingo, Gio, Bambara, Vai, Gbandi, Mende, Kissi, and many more. Freddy is Mande, as his father is from the Loko people, while his mother is from the Mandingo people. However, his mother’s background also includes African American and Guyanese on her mother’s side. Her father’s lineage stretches back to Mali, Senegal, and Guinea. He was a Sheikh with a peculiar birthright among his people.

In Freddy Will’s mind, he became an Afropolitan after naturalizing in the United States and entering his sixth phase with emigration to Canada. During the fifth phase, he put his music career on hold to pursue other opportunities like his post-secondary education. In Toronto, he returned to music, recording Hip Hop albums, a mixtape, and an EP, and released them independently. He later came in his seventh phase when he moved from Canada to Europe. His emigration gives his Afropolitical perspective.

We also note that he transitioned from rapping to literary writing between his sixth and seventh phases. We focus on his sixth phase, when he recorded and released his albums in Toronto. Freddy has published a book series in Europe and released two albums there. When asked about his transition, he gave three reasons. One was his age. He was in his mid-thirties. Another reason he gave was his influence on the fans. He didn’t want to make music with an adverse impact; the last was to “follow his dream.”

Q: Why do you refer to yourself as an Afropolitan?

Freddy Will: “The best way to describe where I belong is to say I’m an Afropolitan. I feel loyal to all the countries I’ve lived in. Yes, I’m a proud American, but in a way, I’m also Liberian, Gambian, Senegalese, Canadian, Belgian, and even German. It’s a kind of psychological connection. Life has given me a transnational identity with my roots in Sierra Leone.”

Q: Very well. What do you say to those who only want you to represent Sierra Leone?

Freddy Will: “Oh, make no mistake, Afropolitans get criticized. Considering how the system works, everyone won’t get that being an Afropolitan is not an aspiration. Life happens. You keep relocating from country to country. You move around the diaspora. Of course, I’m a Sierra Leonean at heart. We call Sierra Leone ‘the land that we love.’ I sprout from deep roots in Gbendembu. It’s my heritage. Whether people realize it or not, everything I do, every failure or accomplishment, represents Salone.

On the other hand, life goes on. Every Afropolitan feels thankful to the diasporas where we’ve lived. Each one adds something to our experience and character. Our awareness shifts from one culture to another. There’s also that downside where we often don’t fit in as newcomers after living in a different country. Sometimes the only hope is to go back to our roots so we grasp our culture. You know what I mean? That’s why I identify as an Afropolitan. It’s the best way to understand people who live like we do.”

Q: Speaking about roots, we learned that your grandfather was a Sheikh with connections to Mali, Senegal, and Guinea, and your grandmother was African American with ties to Guyana. You straddle Africa, the Caribbean, and the United States.

Freddy Will: “Yes. There were a lot of mixed marriages. My mother’s father, Alhaji Sheikh Abdul Gardrie, was a Mandingo. These are the people who founded the Mali Empire. When you trace his lineage, it goes from Senegal to Mali and from Guinea to Sierra Leone. I’m still determining the Yoruba part, but it’s there. Even my last name, Kanu, is primarily Nigerian. I’m figuring out how this Nigerian last name ended up in Sierra Leone. But that’s on my father’s side. The Yoruba is on my mom’s side.

Our family, we even have relatives in Canada now. The Kanu lives there too. Plus, Canada plays a significant role in Sierra Leone’s history. Yes, my mother’s mom was African American. I don’t remember exactly, but they say my grandma’s mom was Guyanese, and her dad was African American. On my father’s side, we’re from a place called Gbendembu. The Loko and the Mandingo are sub-groups of the Mande ethnic group. Some are Muslims, while others are Christians. I’m all that culture in my lineage.”

Q: Tell us about your music. How would you describe it?

Freddy Will: “My music expresses cultural, religious, political, and social experiences. Sometimes it’s a celebration, and other times it’s a howling. At the core, it’s Hip Hop. This genre has shaped many aspects of me. I rap in most of the music. Although, on the production end, the sound could be more assorted. I’d describe my music as a crossover Hip Hop.”

Q: How were you introduced to music?

Freddy Will: “Before he became a born-again Christian, my father used to play music in the house. Back in Liberia, he had an entertainment system. It had a record player. He had many records. My parents threw parties, if I remember correctly. Our neighbors did the same thing. Liberia was a very musical place when I was growing up. Every birthday came with a party, with lots of music and dancing. When my parents converted to born-again Christianity, the music changed to Gospel but still music.”

Q: Were you in the Church choir?

Freddy Will: “No. I’ve always been an outcast. I don’t fit in, so I do my thing. That was the same case in the Church. The choir was there, but I couldn’t get in. I’d watched them sing. I watched them practice, but they didn’t let me join. For me, the answer was always no. Although when I lived in Bo, they had a youth group at our Church. I wasn’t a full member, but once, they let me participate in a convention where we sang on stage and acted in a play from the Bible. It was nice. I was never in the choir.”

Q: You didn’t like Church.

Freddy Will: “I wouldn’t say that. I wasn’t in the groups. I could sit in the audience. The Church in Bo was the best of them. They let me attend or participate in group meetings. I wasn’t a full-fledged member, but I affiliated. As I said, that one time when they had that big convention when all the other Churches met in Bo, and they sent singing groups to represent them, my Church let me participate. I was the kid who hung around watching. During those years, it was all about me wishing and hoping.”

Q: How did you learn how to compose music?

Freddy Will: “I taught myself. I was already rapping before moving to Sierra Leone. I hung around the youth meetings and choir at the new Church, watching them practice. Then I studied the formats in hymn books. I’d ask the guitar or piano player to show me a thing or two every chance I got. Then I’d beatbox the rest. I created the music in my mind. Once my friends put me onto Gangsta rap, I started lip-syncing over instrumentals. As time went on, I started to hear songs in my mind. Randomly, a new song would come to me.”

Q: Who writes and composes your songs?

Freddy Will: “I wasn’t kidding when I said I never fit in anywhere. Okay, maybe I exaggerated a tiny bit. But no, I didn’t get the mentor or the protégé. Most times, when someone showed, they were there to defeat me. I had to write my lyrics. A beatmaker or producer would back me up on the production end. The song comes to my mind, and I’d beatbox the rhythm to myself while writing the lyrics. Then I’d find a producer and hint at a rhythm for the song. Then they’d hit me with whatever they’ve got.”

Q: Take us through your creative process.

Freddy Will: “I watched the choir practice. I’d studied the lyrics in hymn books. Then I taught myself to use the same format. On the rapping side, I learned how to lip sync a few popular songs like ‘Around the Way Girl’ by L. L. Cool J, ‘OPP’ by Naughty by Nature, ‘Down with The King’ by RUN DMC, and ‘Lord Knows’ by Tupac Shakur. Once I could freestyle the lip-synced lyrics, I started to rap them over their instrumental. Shortly after that, I made up my raps and spat them to the instrumental with the hook.

This was between the early to mid-90s. By the mid to late 90s, I was writing lyrics. Now the music comes to me like a download. I hear the song (in my mind) and replicate it. Sometimes I produce it exactly, and other times it turns out differently. Perhaps I was sleeping and dreaming when a song came, and I wrote it down and made a reference recording. Or, I’d listened to a beat, and the song came instantly. At the very least, I’d have written the lyrics if I couldn’t remember the melody or the rhythm.

The chorus or the hook comes first, then the verses. Depending on the producer or engineer, the song could be whatever. With an excellent producer, I’d hint at a drumline, harmony, or baseline, and he’ll take it from there. A beat-making producer might already have a beat where I’d match my hook and verses to his rhythm and adjust. Then I’d take that to the studio. It all depends on the situation. I can rap to any beat and do several genres. It’s a typical format that most artists use to create songs.”

Q: Does that explain the crossover claim you make?

Freddy Will: “The crossover is between two or more genres on the same song. I’d go with Funk, Soul, R&B, Gospel, Reggae, Calypso, Soca, Africana, Classical, Dancehall, Rock, or Country music. Africana music splits into branches like Sukus, Gumbay, Zouk, and Afrobeat. When you bring all that to Hip Hop, you end up with the Afropolitan sound. It’s crossover. That’s like what Afrobeat is in some cases. It’s a work in progress. I’m still looking to make that perfect crossover but blending genres is it.

As I’ve said earlier, the songs come to my mind. I could be cleaning the kitchen, walking, or sleeping. The rhythm comes, I beatbox it, then the rap lyrics start to flow. I’d have a new song if I could find a pen and pad quick enough to write it down and a recorder to freestyle a reference recording. Later, I’ll rewrite and edit it. On the production side, I’d either make the beat or choose a beatmaker’s beat. When everything felt right, I’d go to a studio and record what I’d been working on the last few weeks or so.”

Q: Can you name six of your crossover songs?

Freddy Will: “Yes. ‘City Boy,’ ‘Maria,’ ‘Providence,’ ‘Girl from Happy Hill,’ ‘Pickin,’ and ‘While I’m Still Young.’ I started making crossovers when it was unpopular. People used to criticize it. When I first recorded ‘City Boy,’ many people didn’t get it. The term is a popular slogan now; everyone’s making some crossover. It became a trend years later. I’m not saying they got it from me. I’m saying I was heading in the right direction with that.”

Q: Nice! Tell the fans about your first release.

Freddy Will: “’Stay True.’ We released it off of an independent label in Toronto. I said we because I was with a music producer and his team. It had been almost a decade since I’d rapped or performed professionally. A stroke of luck found me out there, recording my debut album. It was like a dream. He was the producer. I loved his sound. It was perfect for my style. That’s when we recorded ‘Animal,’ ‘So Hard,’ ‘Somebody…’”

Q: We’ve seen rappers who freestyle a song instantly. They have such an intense work ethic that they can write and record several pieces in one go. Are you one of them?

Freddy Will: “I’ve written and recorded two to three songs on the same day and performed them on the same night. I’ve created dope pieces that way. Lately, I don’t prefer that method anymore. As I said, songs come to me. Someone can invite me to a studio, an engineer plays a beat, and they ask me to get in the booth. I would. Typically, the message will not be positive when I spit off the top of my head or write a song within minutes in the studio. That’s where you’d hear all sorts of profanities and shit.

Once I’m peer-pressured to make a quick song, the lyrics go in the stereotypical direction. You’ll get the streets – being inebriated, debauchery, wealthy, or violent situations. When I take my time to write, I’m more thought-provoking. I prefer working on a song for a few days or weeks before recording it. Once we record, that’s it. Once we release it, that’s it. I get songs, write them, and record them at the studio. I could bring two or three to a session and record them simultaneously.” …TO BE CONTINUED.

This article contains branded content provided by a third party. The views expressed in this article are solely those of the content creator or sponsor and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or editorial stance of Popular Hustle.

You may like

-

Milovay Is Done Starting Over and Just Getting Started

-

Andre Correa’s New Single “Histórias” Explores How Stories Change in the Telling

-

Miixed Realities Proves Medical Billing Doesn’t Have to Be a Black Hole

-

GMDCASH Talks Comebacks, Jail Time, and Why He’s Just Getting Started

-

Meet Lil Deezull, the Cambridge Rapper Finding His Moment

-

Dennis Dewall Reboards the Spy Genre with International Thriller ‘THE TRAIN’

Entertainment

Milovay Is Done Starting Over and Just Getting Started

Published

2 days agoon

February 28, 2026

There’s a version of Brandon Serrano that never would’ve landed this article. He spent years pushing names that weren’t working, watching his friends hype him up while the numbers refused to move. It took him a while to figure out the problem wasn’t the music. It was everything around it.

Now he goes by Milovay, and the difference is pretty obvious once you hear the self-titled EP he dropped February 20th.

The four-track project clocks in just under 13 minutes, but it doesn’t feel rushed or underdeveloped. “Finally Open,” “Silver Lining,” “Battle of the Two-Heads,” and “What I Need” each hold their own weight, and the sequencing gives the thing a genuine arc. That’s harder to pull off in a short format than people think. A lot of artists cram four songs together and call it an EP. Milovay actually built something.

The Worcester, Massachusetts native’s R&B and Afro-fusion sound pulls from a pretty specific but interesting set of influences. He’ll tell you Tech N9ne got him hooked on music as a teenager, the speed rapping, the engineer involvement, the obsessive fan connection. But the vocal style owes more to Tory Lanez, that raspy-to-high register range with layered harmonies underneath. It’s a recognizable template, but Milovay doesn’t just ape it. The execution feels considered, not borrowed. And “Silver Lining” is where that execution gets a visual to match it. The song itself is about that specific kind of overthinking that comes with trying to impress someone, not knowing if you’re giving too much or not enough, stuck somewhere between grand gestures and playing it cool.

The video, shot and edited by @trill_is_bliss and featuring co-star @tesqhila, plays that tension straight. There’s no melodramatic breakup, no fantasy sequence. It’s the uncomfortable middle ground the song is actually about, wanting to go all in but second-guessing every move. That’s a harder thing to visualize than heartbreak, and it works.

This is his second EP in just a few months. He dropped “The Lost Scripts of Phenoxism” back in December 2025, and the new one clearly goes in its own direction. That kind of output discipline is notable. Short-form projects released consistently are the current play for independent artists trying to stay relevant without burning through a full album rollout budget, and Milovay seems to genuinely understand the logic of it rather than just following a trend.

He’s also pretty candid about the rebranding process. Years under names that weren’t working, surrounded by yes-people who convinced him the problem was elsewhere. It’s a familiar story in independent music, maybe more common than people admit. What’s worth noting is that he doesn’t frame the past as wasted time. “Peregrine,” “Punani Papi,” all of it, he sees as part of what built him. The willingness to own every version of yourself instead of pretending they didn’t happen is actually rarer than the rebrand itself.

“There is no deadline to make it in this industry,” he said. “I could be 41 and still make moves as if I’ve been doing this for X amount of years.” He means it. Part of what changed is practical too. He talks about finally understanding how to navigate blogs, push his releases correctly, and use social media as an actual tool rather than an afterthought. For independent artists in 2026, that gap between talent and platform literacy is where careers stall. Milovay figured out which side of that gap he needed to close.

Right now the focus is purely on releasing and promoting. No tour dates, no spoilers on what’s coming this summer, though he hints it’ll be worth paying attention to. For a catalog that’s only a few months old under the current name, there’s already a real foundation here.

You can follow Milovay on YouTube, Instagram, and stream his music on Spotify, Apple Music, and SoundCloud.

Entertainment

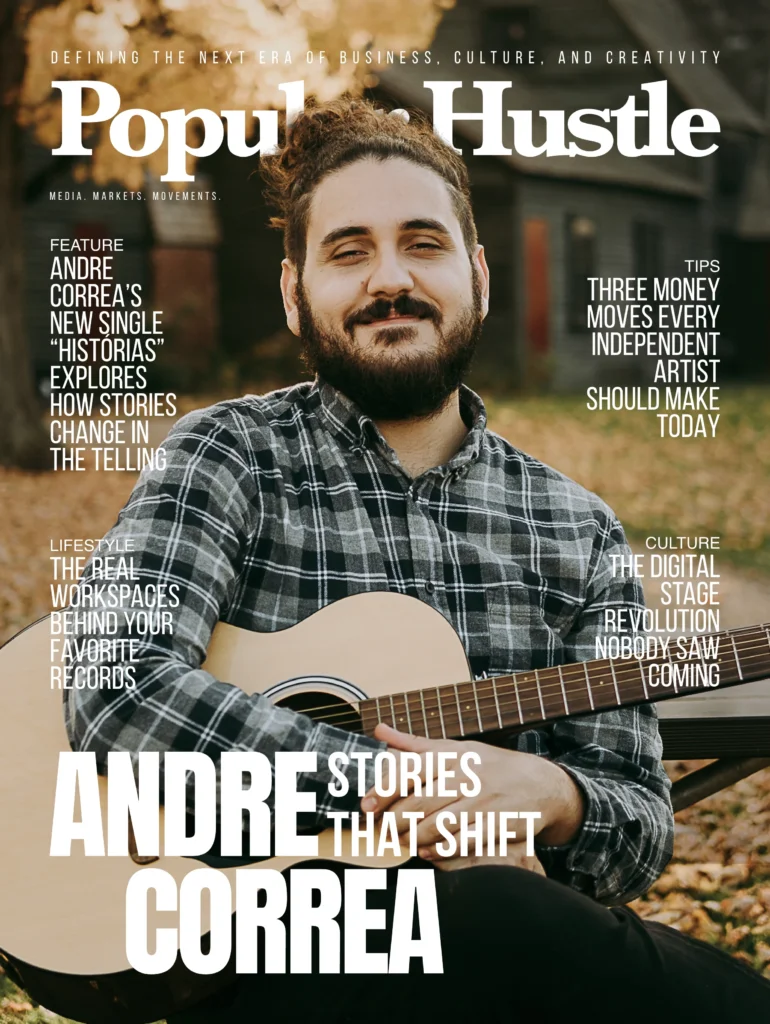

Andre Correa’s New Single “Histórias” Explores How Stories Change in the Telling

Published

4 weeks agoon

February 2, 2026

The best instrumental music makes you feel something you can’t quite name. Brazilian guitarist Andre Correa’s new single “Histórias” works like that, building a narrative without a single word by exploring how stories transform as they pass between people.

The track, which translates to “Stories” in English, draws from baião and fusion to create something that unfolds like a conversation you’re overhearing. Correa structured the composition around the concept of a game of telephone, where a single idea gets reinterpreted through different emotional filters until it returns to something clearer than where it started. The piece swells and contracts, moving through restlessness and conflict before landing somewhere more settled and direct.

“The work invites the listener to create their own interpretation,” Correa explains. “Each person hears a different story within the same music.”

It’s a fitting approach for a guitarist who treats composition as personal archaeology. Correa, a Berklee College of Music graduate now based in Orlando, doesn’t start with theory or structure when he writes. He starts with whatever he’s actually living through, picking up his guitar and trying to translate feeling into sound. One idea leads to another until the piece reveals its own direction. “I only feel comfortable when I can see the full picture and everything feels cohesive, like the music is telling one clear story,” he says.

That process shaped his debut album “Seasons,” released November 29, 2025, which documents his years in Boston through seven original tracks. But “Histórias,” releasing in 2026, pushes further into abstraction, examining not just personal experience but the nature of how experience gets communicated and distorted over time. Multiple musical “voices” emerge from a single theme, creating layers that explore the relationship between noise, interpretation, and truth.

Correa was born in Valinhos, São Paulo, and raised in Campinas, learning keyboard from his father at eight before picking up guitar at twelve. Playing in church communities taught him early that music works best as service rather than spectacle, a belief that stuck through his formal training at Berklee, where he studied with faculty including Danilo Pérez, John Patitucci, and Randy Roos. His time at the Berklee Global Jazz Institute took him into hospitals and rehabilitation centers, reinforcing his sense that music exists to create space for something meaningful to happen.

The immigrant experience of rebuilding life in the United States has informed his writing as much as any classroom. Moving countries, learning to navigate unfamiliar systems, processing the particular loneliness of starting over in a new place: all of it feeds into work that prioritizes emotional honesty over technical display.

“I don’t think of my work as just songs or compositions,” Correa says. “I think of each piece as a small narrative, a space where melody, harmony, rhythm, and improvisation work together to express something human: faith, doubt, change, longing, gratitude, conflict, hope.”

Beyond his recording projects, Correa is preparing to launch an educational book series called “The Ultimate Guide,” with the first volume, “Major Pentatonic: The Ultimate Guide,” scheduled for release in January 2026. The series applies his FCA Method, a framework focused on helping guitarists develop their own musical identity rather than just memorizing patterns. He currently performs regularly at Jazz Tastings in Orlando, where he develops his sound and refines his artistic direction in a live setting.

Correa isn’t chasing anything grand with his music. If someone walks away feeling a little more present, a little more honest with themselves, or simply more connected to their own emotions, he figures the work has done what it was supposed to do.

“Histórias” rewards that kind of attention. The track doesn’t demand you understand it on first listen. It just asks you to sit with it long enough to find whatever story you needed to hear.

Stream Andre Correa’s music on Spotify and Apple Music, and follow his work on Instagram, YouTube, Facebook, TikTok, and LinkedIn. Visit his website for more.

Entertainment

GMDCASH Talks Comebacks, Jail Time, and Why He’s Just Getting Started

Published

1 month agoon

January 19, 2026

Some artists talk about grinding. Others actually live it. Calvin Davenport, better known as GMDCASH, falls squarely into the second category. The Seattle-born rapper has navigated the kind of obstacles that would make most people quit, including incarceration, legal restrictions on his content, and the predatory side of an industry that loves to take advantage of independent artists. He’s still here, though, and with previous coverage in outlets like Earmilk and The Source already under his belt, his recent output suggests he’s figured out how to turn setbacks into fuel.

His latest single “Bump A Whore Pt. 2,” released January 16th, 2026, sees him team up with MikeJack3200 and Frostydasnowmann for a polished follow-up to the original. But it was his comeback track “I’m The Product,” dropped at the top of the year, that set the tone. That title isn’t just a song name. It’s a thesis statement. The track positions GMDCASH as someone who’s done waiting for opportunities to find him. Instead, he’s become the opportunity. With a new EP on the way, he’s building momentum on his own terms.

We caught up with GMDCASH to talk about what drives him, how he creates, and what’s next.

Take us back to a specific moment when you knew this was what you were going to do. What happened?

I think after getting out of jail I geared my focus towards my music career. I really needed a positive outlet, something that woke me up, drove me, and inspired me and the people around me. Music did that for me.

If someone’s never heard your music before, how would you describe what you do?

I would say my music is for everyone. I have a pretty big catalog and it’s forever expanding, so if you don’t hear something you like, check back every now and again. I’m sure something will catch your ear. And if not, it’s more than music. It’s my life story. I want people to be inspired by my music. I want people to hear it and know that anything is possible.

Who or what shaped your creative voice the most?

My family is a big part of my influence. Both my parents and some of my family members have been in the industry. Growing up in a musical household is number one. I have a unique style. I couldn’t say one thing shaped my creative voice, and I feel like my creativity is forever changing every time I’m in the studio.

Walk us through how you actually create.

Honestly, I book a session and spend four hours minimum in the studio. Sometimes I don’t even book. I’ll just feel something and call a studio and get to work. Most beats are made as soon as I pull up. The producer gives me the sample, I approve, he starts the loop. Most of my lyrics are life experience, so it’s not hard for me to make a song. I just rap how I’m feeling. Sometimes it’s a smooth process, others take time. Then they mix and master and I schedule the release.

What’s something you had to figure out the hard way?

I think going to jail at the end of the year was really a wake up call. I have to protect myself and keep people around me who want what’s really best for me, not just have anyone around me.

Is there anyone you’d love to work with down the line?

I really would like to collab with Hurricane Wisdom.

Where are you at in your music career right now?

This is just the beginning. I feel there’s so much more to come. Music is my passion. I don’t think I’m leaving the mic anytime soon.

What are you working on that you’re excited about?

I’m excited for my next EP coming out early this year. I focused on songs with uplifting, positive energy and the GMD, Get Money Daily, vibe. I’m hoping to do at least two shows before the middle of the year. I’m just excited about the possibility of the new year and all the good things it has to bring.

If there’s one thing you want readers to take away from this feature, what is it?

I’m an up and coming Seattle rapper. Check out my music, be inspired, follow my page, interact, share your thoughts.

What stands out about GMDCASH isn’t the adversity itself. Plenty of artists have tough stories. It’s the clarity that came out of it. He’s not chasing validation or waiting for a label to cosign his vision. Beyond music, he has plans to move into artist management and eventually relocate abroad. For listeners who connect with authenticity over polish, that long-term thinking is the whole point.

Stream GMDCASH on Spotify, Youtube, and Apple Music, visit his official website, and follow him on Instagram.

Milovay Is Done Starting Over and Just Getting Started

Andre Correa’s New Single “Histórias” Explores How Stories Change in the Telling

Miixed Realities Proves Medical Billing Doesn’t Have to Be a Black Hole

GMDCASH Talks Comebacks, Jail Time, and Why He’s Just Getting Started

Meet Lil Deezull, the Cambridge Rapper Finding His Moment

Dennis Dewall Reboards the Spy Genre with International Thriller ‘THE TRAIN’

Saynt Ego on Grief, Mental Health, and Learning to Sit With the Noise

Marloma Talks Learning to Stop Writing in Isolation and Trust the Chaos

Zizzo World Is Building Momentum That’s Hard to Ignore

Yash Kapoor Wants His Records To Feel Like Moments, Not Just Music

Inside the Amazon Reinstatement Process: The aSellingSecrets Approach

Golden Bay Beach Hotel — A Luxury Beachfront Escape in Larnaca, Cyprus

Nodust Writes His Lyrics Last and That’s Exactly the Point

Finding Strength in Walking Away Is the Real Message Behind Judy Pearson’s New Single

Joaquina’s “Freno” Captures the Push and Pull of Letting Go

Jason Luv Dominates Charts While Inspiring New Wave of Multi Career Artists

Harley West | Inside the Mind of a Social Media Star on the Rise

Raw Fishing | Franklin Seeber, Known As “Raww Fishing” Youtuber Story

Jordana Lajoie Transforms Montreal Roots into Hollywood Success Story

A New Hollywood Icon Emerges in Madelyn Cline

Who is Isaiah Silva – The Story Behind The Music

Tefi Valenzuela Pours Her Heart into New Song About Breaking Free

G FACE Releases His New Single “All up,” and It’s Fire

Gearshift to Stardom: Nikhael Neil’s Revolutionary Journey in the Automotive Industry

Kaia Ra | Perseverance That Built a Best-Selling Author

Holly Valentine | Social Media Influencer & Star Success Story

Kate Katzman | Breaking Into Hollywood and Embracing Change

Thara Prashad | Singer Evolves to Yoga & Mediation Superstar

Tadgh Walsh – How This Young Entrepreneur is Making a Name for Himself

King Lil G | West Coast Hip Hop Genius Rises to Face With Ease

Tefi Valenzuela Pours Her Heart into New Song About Breaking Free

Kate Katzman | Breaking Into Hollywood and Embracing Change

Holly Valentine | Social Media Influencer & Star Success Story

Kaia Ra | Perseverance That Built a Best-Selling Author

Lil Ugly Baby XXX’s “Who?” – The Mixtape to Boost Your Playlist

Samuel Chewning Explains How Fitness Should Be A Personal Journey

Trending

-

Business4 years ago

Business4 years agoJason Luv Dominates Charts While Inspiring New Wave of Multi Career Artists

-

Entertainment3 years ago

Entertainment3 years agoHarley West | Inside the Mind of a Social Media Star on the Rise

-

Culture4 years ago

Culture4 years agoRaw Fishing | Franklin Seeber, Known As “Raww Fishing” Youtuber Story

-

Culture3 years ago

Culture3 years agoJordana Lajoie Transforms Montreal Roots into Hollywood Success Story

-

Culture2 years ago

Culture2 years agoA New Hollywood Icon Emerges in Madelyn Cline

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year agoWho is Isaiah Silva – The Story Behind The Music

-

Entertainment3 years ago

Entertainment3 years agoTefi Valenzuela Pours Her Heart into New Song About Breaking Free

-

Culture4 years ago

Culture4 years agoG FACE Releases His New Single “All up,” and It’s Fire