Entertainment

Norwegian Brothers Release Their Most Ambitious Album Yet With ‘Dreams and Conjurations’

Published

4 months agoon

When Sturle Dagsland describes conducting a two-hundred-dog choir in Greenland, he’s not joking. The Norwegian artist, who makes up half of the sibling duo behind the project, actually positioned himself in the middle of a small village, set up microphones, and got the sled dogs to respond to his howls like an orchestra following a conductor’s baton. That recording session tells you everything about how this project works: experimental, adventurous, and rooted in a genuine connection to the natural world.

Sturle and Sjur Dagsland released their second album, Dreams and Conjurations, on October 10, 2025. The brothers, based in Stavanger, Norway, have built their sound around an unusual combination: Sámi folk traditions from their northern Norwegian heritage mixed with instruments from around the world. On any given track, you might hear Swedish nyckelharpa, Norwegian goat horn, Chinese guzheng, West African kora, Hungarian cimbalom, and waterphone, all woven together with modern recording techniques and electronic elements.

Their 2021 self-titled debut earned them an Edvard Award for best Norwegian album of the year. The new record pushes even further, mixing avant-garde pop, folk music, metal intensity, and electronic soundscapes. It’s not the kind of album that fits comfortably into one genre, and that’s exactly the point.

The brothers see limiting themselves to one feeling or genre as dishonest. They’re not interested in playing just one style. They’d rather move through different emotions and let the music breathe in whatever direction feels right.

Their approach to Norwegian traditions comes through in songs like “Hallingen,” named after a folk dance that Sturle compares to Norwegian breakdancing. Dancers spin, flip, and jump to kick a hat off a stick. A few years ago, they performed at a museum opening with a halling dancer, creating music that captured the rhythm and energy of the tradition without being a strict replica. They also incorporated elements from their Sámi heritage, blending vocal styles and rhythms from their family background into something new.

The recording locations are worth noting. The brothers don’t stick to traditional studios. They’ve captured sounds in abandoned ships, remote villages, stormy clocktowers, and a water tower in Berlin’s Prenzlauer Berg neighborhood. Sjur points out that the Berlin space has a long reverb that inspires them to play differently. The acoustics actually change how they approach their instruments.

One of the album’s songs, “Whispering Forest, Echoing Mountains,” came from a chance encounter in Beijing. While touring China, they met a half-blind elderly man playing guzheng near the Forbidden City. He invited them to his home, told them he’d dreamed of Norwegian mountains despite never leaving China, and they jammed with him all night while his family brought dinner. The experience inspired one of the most-used instruments on the album.

Their collection of international instruments raises questions about cultural appropriation, but Sturle’s perspective is straightforward. Instrument makers are usually happy to see their creations being played and want their traditions to live on. He uses the guzheng in ways that don’t sound traditional at all. It’s about exploration and spreading the joy of music rather than claiming mastery or authenticity.

Working as siblings has its challenges. They used to share a tiny studio that doubled as Sjur’s bedroom, sleeping and creating music in the same cramped space. These days they live separately, though they’re still neighbors on the same street. The brothers perform mostly as a duo, though they’ll occasionally bring in dancers, visual artists, or multi-instrumentalist friends for special shows.

Looking ahead, they’re planning tours across Europe, Japan, Korea, Mexico, and Brazil. Sturle has bigger dreams too. He wants to create a musical with a fantastic director, where he’d perform all the character voices in different styles. It would be surreal and fairytale-like, something imaginative and playful. Sjur has already decided his role: he’d be on a flying carpet.

For now, Dreams and Conjurations offers plenty: ambient whispers on “Windharp,” ceremonial chaos on “The Ritual,” and ghostly minimalism on “Kwaidan.” It’s music that doesn’t ask for passive listening. It demands you lean in and pay attention.

You can stream the album and follow Sturle Dagsland on Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube.

Indie music journalist digging up the stuff algorithms overlook. No industry fluff, just honest takes and good music. Self-taught, self-published, doing it for the love, not the clicks.

You may like

-

Andre Correa’s New Single “Histórias” Explores How Stories Change in the Telling

-

Miixed Realities Proves Medical Billing Doesn’t Have to Be a Black Hole

-

GMDCASH Talks Comebacks, Jail Time, and Why He’s Just Getting Started

-

Meet Lil Deezull, the Cambridge Rapper Finding His Moment

-

Dennis Dewall Reboards the Spy Genre with International Thriller ‘THE TRAIN’

-

Saynt Ego on Grief, Mental Health, and Learning to Sit With the Noise

Entertainment

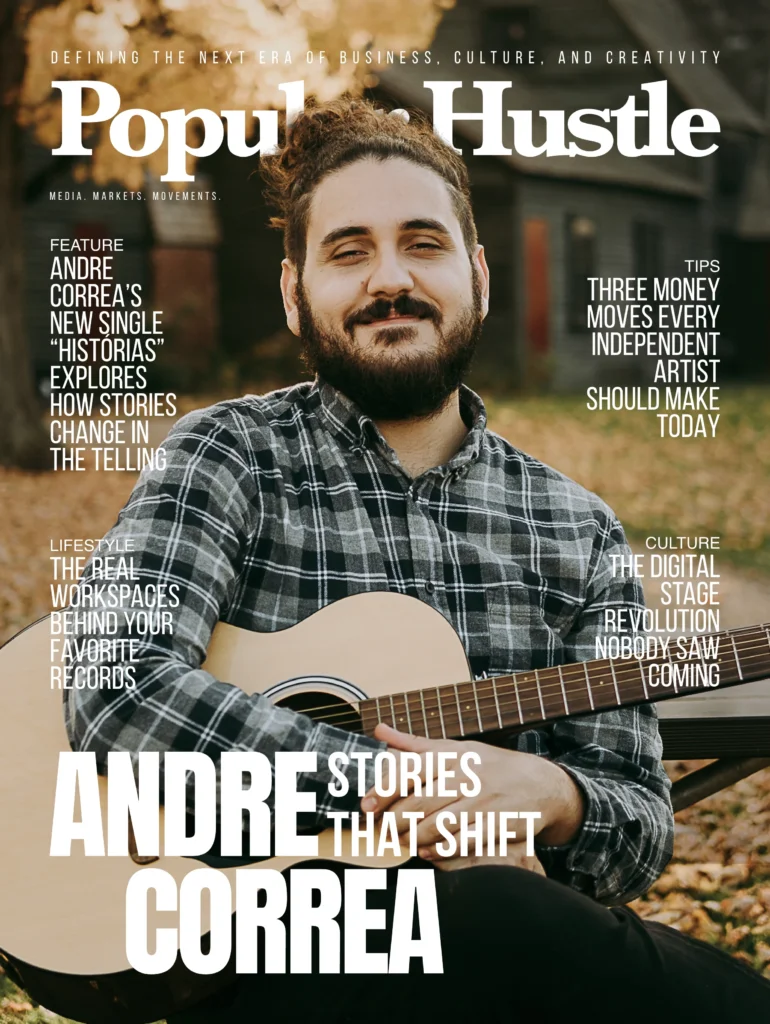

Andre Correa’s New Single “Histórias” Explores How Stories Change in the Telling

Published

6 hours agoon

February 2, 2026

The best instrumental music makes you feel something you can’t quite name. Brazilian guitarist Andre Correa’s new single “Histórias” works like that, building a narrative without a single word by exploring how stories transform as they pass between people.

The track, which translates to “Stories” in English, draws from baião and fusion to create something that unfolds like a conversation you’re overhearing. Correa structured the composition around the concept of a game of telephone, where a single idea gets reinterpreted through different emotional filters until it returns to something clearer than where it started. The piece swells and contracts, moving through restlessness and conflict before landing somewhere more settled and direct.

“The work invites the listener to create their own interpretation,” Correa explains. “Each person hears a different story within the same music.”

It’s a fitting approach for a guitarist who treats composition as personal archaeology. Correa, a Berklee College of Music graduate now based in Orlando, doesn’t start with theory or structure when he writes. He starts with whatever he’s actually living through, picking up his guitar and trying to translate feeling into sound. One idea leads to another until the piece reveals its own direction. “I only feel comfortable when I can see the full picture and everything feels cohesive, like the music is telling one clear story,” he says.

That process shaped his debut album “Seasons,” released November 29, 2025, which documents his years in Boston through seven original tracks. But “Histórias,” releasing in 2026, pushes further into abstraction, examining not just personal experience but the nature of how experience gets communicated and distorted over time. Multiple musical “voices” emerge from a single theme, creating layers that explore the relationship between noise, interpretation, and truth.

Correa was born in Valinhos, São Paulo, and raised in Campinas, learning keyboard from his father at eight before picking up guitar at twelve. Playing in church communities taught him early that music works best as service rather than spectacle, a belief that stuck through his formal training at Berklee, where he studied with faculty including Danilo Pérez, John Patitucci, and Randy Roos. His time at the Berklee Global Jazz Institute took him into hospitals and rehabilitation centers, reinforcing his sense that music exists to create space for something meaningful to happen.

The immigrant experience of rebuilding life in the United States has informed his writing as much as any classroom. Moving countries, learning to navigate unfamiliar systems, processing the particular loneliness of starting over in a new place: all of it feeds into work that prioritizes emotional honesty over technical display.

“I don’t think of my work as just songs or compositions,” Correa says. “I think of each piece as a small narrative, a space where melody, harmony, rhythm, and improvisation work together to express something human: faith, doubt, change, longing, gratitude, conflict, hope.”

Beyond his recording projects, Correa is preparing to launch an educational book series called “The Ultimate Guide,” with the first volume, “Major Pentatonic: The Ultimate Guide,” scheduled for release in January 2026. The series applies his FCA Method, a framework focused on helping guitarists develop their own musical identity rather than just memorizing patterns. He currently performs regularly at Jazz Tastings in Orlando, where he develops his sound and refines his artistic direction in a live setting.

Correa isn’t chasing anything grand with his music. If someone walks away feeling a little more present, a little more honest with themselves, or simply more connected to their own emotions, he figures the work has done what it was supposed to do.

“Histórias” rewards that kind of attention. The track doesn’t demand you understand it on first listen. It just asks you to sit with it long enough to find whatever story you needed to hear.

Stream Andre Correa’s music on Spotify and Apple Music, and follow his work on Instagram, YouTube, Facebook, TikTok, and LinkedIn. Visit his website for more.

Entertainment

GMDCASH Talks Comebacks, Jail Time, and Why He’s Just Getting Started

Published

2 weeks agoon

January 19, 2026

Some artists talk about grinding. Others actually live it. Calvin Davenport, better known as GMDCASH, falls squarely into the second category. The Seattle-born rapper has navigated the kind of obstacles that would make most people quit, including incarceration, legal restrictions on his content, and the predatory side of an industry that loves to take advantage of independent artists. He’s still here, though, and with previous coverage in outlets like Earmilk and The Source already under his belt, his recent output suggests he’s figured out how to turn setbacks into fuel.

His latest single “Bump A Whore Pt. 2,” released January 16th, 2026, sees him team up with MikeJack3200 and Frostydasnowmann for a polished follow-up to the original. But it was his comeback track “I’m The Product,” dropped at the top of the year, that set the tone. That title isn’t just a song name. It’s a thesis statement. The track positions GMDCASH as someone who’s done waiting for opportunities to find him. Instead, he’s become the opportunity. With a new EP on the way, he’s building momentum on his own terms.

We caught up with GMDCASH to talk about what drives him, how he creates, and what’s next.

Take us back to a specific moment when you knew this was what you were going to do. What happened?

I think after getting out of jail I geared my focus towards my music career. I really needed a positive outlet, something that woke me up, drove me, and inspired me and the people around me. Music did that for me.

If someone’s never heard your music before, how would you describe what you do?

I would say my music is for everyone. I have a pretty big catalog and it’s forever expanding, so if you don’t hear something you like, check back every now and again. I’m sure something will catch your ear. And if not, it’s more than music. It’s my life story. I want people to be inspired by my music. I want people to hear it and know that anything is possible.

Who or what shaped your creative voice the most?

My family is a big part of my influence. Both my parents and some of my family members have been in the industry. Growing up in a musical household is number one. I have a unique style. I couldn’t say one thing shaped my creative voice, and I feel like my creativity is forever changing every time I’m in the studio.

Walk us through how you actually create.

Honestly, I book a session and spend four hours minimum in the studio. Sometimes I don’t even book. I’ll just feel something and call a studio and get to work. Most beats are made as soon as I pull up. The producer gives me the sample, I approve, he starts the loop. Most of my lyrics are life experience, so it’s not hard for me to make a song. I just rap how I’m feeling. Sometimes it’s a smooth process, others take time. Then they mix and master and I schedule the release.

What’s something you had to figure out the hard way?

I think going to jail at the end of the year was really a wake up call. I have to protect myself and keep people around me who want what’s really best for me, not just have anyone around me.

Is there anyone you’d love to work with down the line?

I really would like to collab with Hurricane Wisdom.

Where are you at in your music career right now?

This is just the beginning. I feel there’s so much more to come. Music is my passion. I don’t think I’m leaving the mic anytime soon.

What are you working on that you’re excited about?

I’m excited for my next EP coming out early this year. I focused on songs with uplifting, positive energy and the GMD, Get Money Daily, vibe. I’m hoping to do at least two shows before the middle of the year. I’m just excited about the possibility of the new year and all the good things it has to bring.

If there’s one thing you want readers to take away from this feature, what is it?

I’m an up and coming Seattle rapper. Check out my music, be inspired, follow my page, interact, share your thoughts.

What stands out about GMDCASH isn’t the adversity itself. Plenty of artists have tough stories. It’s the clarity that came out of it. He’s not chasing validation or waiting for a label to cosign his vision. Beyond music, he has plans to move into artist management and eventually relocate abroad. For listeners who connect with authenticity over polish, that long-term thinking is the whole point.

Stream GMDCASH on Spotify, Youtube, and Apple Music, visit his official website, and follow him on Instagram.

Entertainment

Meet Lil Deezull, the Cambridge Rapper Finding His Moment

Published

2 weeks agoon

January 19, 2026

Some artists spend years waiting for their moment without realizing it already came and went. Lil Deezull knows what that feels like. He’s been rapping since 2015, freestyling with friends in Cambridge, Maryland long before he thought of it as a career. It took seven years and a viral track before he understood what he’d been sitting on.

The Cambridge rapper, born August 16, 2005, didn’t start out with a plan. His first actual track, “Big Booty,” got passed around locally and gave him his first taste of what connecting with an audience felt like. But it wasn’t until 2022 that everything clicked. A track called “Purple Rain” went viral, and suddenly the kid who’d been rapping for fun had people actually paying attention.

“Since then I started taking my music career seriously,” Lil Deezull says. That shift shows in his output. His 2024 album, For All The Snow Bunnies, marked his biggest project to date and helped establish him beyond his Eastern Shore hometown.

The numbers tell part of the story. His track “Suffering” has pulled over 106,000 plays with solid engagement, while newer releases like “NO KINGS” show he’s building consistent momentum rather than chasing one-off hits. He works primarily in hip-hop and rap, pulling from the melodic trap style popularized by artists like The Kid LAROI and Polo G, but he’s not interested in staying in one lane.

“I am a multi genre artist and I make music for everyone,” he explains. Recently, that’s meant studying country artists like Morgan Wallen, looking for ways to expand his reach beyond rap’s typical audience. It’s an unconventional move for a young rapper from Maryland, but it speaks to how he thinks about his career.

His lyrics draw from personal experience. Daily life, observations, things he sees and hears in Cambridge. He wants listeners to find something relatable.

“My hope is that people will relate to me and that my music can help them get through whatever they are going through in life,” Lil Deezull says.

His next project, Maryland Man, drops May 16 and represents a return to collaboration after a solo-focused 2024. The album features fellow Cambridge rappers Lil Mop and Murda2x alongside international collaborator Brixton, who appeared on For All The Snow Bunnies. It’s a deliberate effort to spotlight his hometown’s scene while building on last year’s momentum.

At 19, Lil Deezull has already been making music for nearly a decade. He’s had time to figure out what he wants to say, and he’s also had time to accumulate regrets. “Don’t be like me and have a life full of missed opportunities,” he says. “Live your life and take any chance you get.”

It’s a surprising bit of self-awareness from someone still early in his career, but it tracks with why he finally got serious after “Purple Rain” took off. He’d spent seven years treating music like a hobby while the moment kept knocking. Now he’s answering the door.

Follow Lil Deezull on SoundCloud, Instagram, and YouTube.

Andre Correa’s New Single “Histórias” Explores How Stories Change in the Telling

Miixed Realities Proves Medical Billing Doesn’t Have to Be a Black Hole

GMDCASH Talks Comebacks, Jail Time, and Why He’s Just Getting Started

Meet Lil Deezull, the Cambridge Rapper Finding His Moment

Dennis Dewall Reboards the Spy Genre with International Thriller ‘THE TRAIN’

Saynt Ego on Grief, Mental Health, and Learning to Sit With the Noise

Marloma Talks Learning to Stop Writing in Isolation and Trust the Chaos

Zizzo World Is Building Momentum That’s Hard to Ignore

Yash Kapoor Wants His Records To Feel Like Moments, Not Just Music

Inside the Amazon Reinstatement Process: The aSellingSecrets Approach

Golden Bay Beach Hotel — A Luxury Beachfront Escape in Larnaca, Cyprus

Nodust Writes His Lyrics Last and That’s Exactly the Point

Finding Strength in Walking Away Is the Real Message Behind Judy Pearson’s New Single

Joaquina’s “Freno” Captures the Push and Pull of Letting Go

Young Romanian Entrepreneur Explores Lisbon’s Thriving Startup Scene

Jason Luv Dominates Charts While Inspiring New Wave of Multi Career Artists

Harley West | Inside the Mind of a Social Media Star on the Rise

Raw Fishing | Franklin Seeber, Known As “Raww Fishing” Youtuber Story

Jordana Lajoie Transforms Montreal Roots into Hollywood Success Story

A New Hollywood Icon Emerges in Madelyn Cline

Who is Isaiah Silva – The Story Behind The Music

Tefi Valenzuela Pours Her Heart into New Song About Breaking Free

G FACE Releases His New Single “All up,” and It’s Fire

Gearshift to Stardom: Nikhael Neil’s Revolutionary Journey in the Automotive Industry

Kaia Ra | Perseverance That Built a Best-Selling Author

Holly Valentine | Social Media Influencer & Star Success Story

Kate Katzman | Breaking Into Hollywood and Embracing Change

Thara Prashad | Singer Evolves to Yoga & Mediation Superstar

Tadgh Walsh – How This Young Entrepreneur is Making a Name for Himself

King Lil G | West Coast Hip Hop Genius Rises to Face With Ease

Tefi Valenzuela Pours Her Heart into New Song About Breaking Free

Kate Katzman | Breaking Into Hollywood and Embracing Change

Holly Valentine | Social Media Influencer & Star Success Story

Kaia Ra | Perseverance That Built a Best-Selling Author

Lil Ugly Baby XXX’s “Who?” – The Mixtape to Boost Your Playlist

Samuel Chewning Explains How Fitness Should Be A Personal Journey

Trending

-

Business4 years ago

Business4 years agoJason Luv Dominates Charts While Inspiring New Wave of Multi Career Artists

-

Entertainment3 years ago

Entertainment3 years agoHarley West | Inside the Mind of a Social Media Star on the Rise

-

Culture4 years ago

Culture4 years agoRaw Fishing | Franklin Seeber, Known As “Raww Fishing” Youtuber Story

-

Culture2 years ago

Culture2 years agoJordana Lajoie Transforms Montreal Roots into Hollywood Success Story

-

Culture2 years ago

Culture2 years agoA New Hollywood Icon Emerges in Madelyn Cline

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year agoWho is Isaiah Silva – The Story Behind The Music

-

Entertainment3 years ago

Entertainment3 years agoTefi Valenzuela Pours Her Heart into New Song About Breaking Free

-

Culture4 years ago

Culture4 years agoG FACE Releases His New Single “All up,” and It’s Fire